Tuesday, January 29, 2008

Sunday, January 13, 2008

Al Green — Amazing Grace

After a dozen years of walking the road to heaven,

the Reverend Al Green raises a little hell.

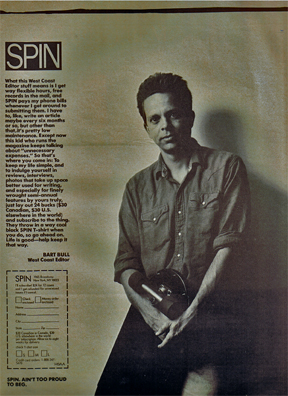

by Bart Bull

(photography by Anton Corbijn)

published in SPIN

White. White teeth — white, white teeth — white tie, white shoes, white pants, white jacket. And in the buttonhole, a red, red rose. Yes, and Al Green is smiling, smiling. Smiling, grinning, glowing — white, white teeth — gleaming and beaming with joy and gold jewelry, glowing with love and happiness.

And Al Green is always beaming, always, even now. Even now. Even now, just a few slim moments before he'll be out on a Northern California concert stage and the seats will be filled with devout churchified ladies from Oakland and Richmond and San Francisco, big broad-boned black ladies and little black ladies with bones like birds, and yes, they well remember all those worldly songs Al Green used to sing back ten or fifteen years ago, "Let's Stay Together" and "Tired of Being Alone" and I'm Still In Love With You," all of those and all of the others. Yes, they remember. But no, they didn't come here tonight, not one of them, to hear Al Green sing those songs. Tonight they came to hear the man who left all that talk of worldly love behind him when he finally took up his calling, when he stopped fighting and surrendered his life and his music to the Lord. Tonight they are ready to hear the Reverend Al Green.

And tonight the Reverend Green is beaming and gleaming backstage, talking with old friends, laughing, laughing. And if the ladies of the audience had been here this afternoon to see the Reverend rehearse his band, they’d have seen him relaxed and laughing, beaming and gleaming and giggling and just having himself a wonderful time working the band through the evergreen glory of “Let’s Stay Together.” Wearing those glasses of his for the scholarly effect, the clear ones with the tiny, tiny pink roses embedded in the frames, and adjusting the singers’ harmonies, squeezing the horns down tighter, teaching the drummer that unbeatable trot, and preparing to sing, tonight, for the first time in all the nine years since he came to Jesus once and all, one of his old songs, his secular songs, his love songs. Yes, and singing, just for a quick little moment, “Let’s . . . let’s stay to-geth-er . . . loving you whether . . . whether . . . times are good or bad, happy or—” before he cut it short, and burst out laughing. Laughing.

And he’s laughing backstage now, just moments to go, slapping his knees and howling high and maybe even looking out of the corner of his eye just a little to see if everyone is appreciating him appreciating the joke. And they should, truly they should, because tonight is like some moment fallen loose from a history book, a page falling across time. Tonight Al Green will step back across a line he has crossed just once before, a line that won’t be crossed too many times.

Sam Cooke crossed this line one time, going the other way. He left the Soul Stirrers, left the mightiest gospel quartet of all , left it to become a big pop star. And he did too, became the biggest of black pop stars, became a manly black symbol of style and sophistication. Yes, but something was missing, something was wrong that he could not right. Didn’t matter how well his worldly career was going, didn’t matter what he did, and so he tried to come back over the line. He went onstage with the Soul Stirrers in Chicago, and first the good gospel folks were silent as the dead and after that they catcalled him right off the stage. Yes, and it wasn’t too many months later that Sam Cooke was shot dead in a Los Angeles auto court. What does it profit a man to gain the world if he loses his soul?

And from the instant the Reverend Green bounces up the steps to this Northern California stage, something is wrong, something isn’t working, some presence, some spirit, is missing. The ladies of the audience are patient but they’re ready too, waiting to be moved, to be shaken and stirred. Yes, and still something is missing, something is empty. Maybe Al Green’s mind is elsewhere, maybe deep in his heart Al Green knows he’s not supposed to mess with those old songs. He hasn’t touched one yet—not yet—but they’re so near at hand. All he has to do right now is call for “Let’s Stay Together” and he’ll have stepped back over that line again.

Those songs are so near at hand, and so are those good gospel-drenched ladies, the ones who have been with him in these years since he came to his calling. “You know,” he tells them, “there are two different kinds of love.” Smiling shyly, slyly, he’s scratching the back of his head and looking up at the lights. “Let’s not ever forget that. Let’s not ever forget that there are two kinds of love, that there’s God’s love and then there’s man’s love, the love of a man for his wife, the love of a wife for her husband. And that’s a righteous love too, because that’s why man and woman was created by God, for love and happiness, so that they would stay together.” And the band has just so very, very sweetly and so very, very softly eased on into a familiar little trot, has slipped into “Let’s Stay Together,” and even the sternest of the ladies can’t help but start to rock in the pews.

Yes, and even though it’s all falling in place for the Reverend Green to lean right back into the open arms of “Let’s Stay Together,” he carries on, he commences, he loosens his tie and continues to testify. A man’s love for a woman, a woman’s love for a man can be a righteous thing, but we all know that God knows when it is and when it is not. Can anyone out there tonight ever say that they have gone and fooled God? No, and it’s only a fool who thinks he can fool God, who thinks he can do any old thing he wants to do, who thinks he can escape from what’s right, from what’s righteous. Does anyone here know what I’m talking about here tonight?

Yes, and the band is still vamping on “Let’s Stay Together,” and before too many minutes the Reverend does grab that song up, goes ahead on and sings the thing but he can’t seem to find the spirit in it. It’s beautiful, it’s sleek as a cat, no one in the world can sing a song like Al Green, no one in all the world, but not this song, not tonight. No.

And it doesn’t matter what he does now, doesn’t matter if he stops and takes off his shoes to get a little more comfortable — he does — and it doesn’t matter if he throws those shoes, throws them deep into the cheap seats — he does—and it doesn’t matter if he sets himself down on the edge of the stage and dangles his stocking feet and lays back on the stage and starts to singing again. No, it doesn’t matter what he does, doesn’t matter that he goes on to sing “Precious Lord” or “He Is the Light,” doesn’t matter that he is Al Green, the Reverend Al Green, the sweetest, finest, greatest singer on God’s green earth, because tonight he isn’t moved, isn’t stirred. Because tonight he can’t find the spirit. And tonight the ladies are going home early.

On the following day, he’s scheduled for a morning taping of Soul Train, though by the time he arrives it’s late afternoon. He and Don Cornelius, the slowest-speaking host in show business, clasp all their hands together like old friends. There was a time when every Al Green song was a hit and every appearance he made on Soul Train was a gift. He sold 20 million records in the early ‘70s, with ten Top 10 hits. But it’s been more than 12 years since the last of those now, and there’s fair reason to believe Cornelius is simply offering an old friend a favor.

Still, if those hits linger in the memory of Don Cornelius, how much respect can be expected of the kids on this afternoon’s Soul Train? The Reverend Green has elected to wear the most conservative of navy blue suits today, in contrast to all the jangling spangled costumes around him; the only things the least bit flashy about him are his gold rings and perhaps the quiet pink roses of his boxy eyeglasses.

The kids dance to his lip-synched version of “You Brought the Sunshine,” — he may be the least interested lip-synch artist in pop music — but they dance to everything once the cameras are on. Everyone, the Reverend Green included, is standing in place so Don Cornelius can muff a few interview lines when out of nowhere a young guy, 17 or so, starts to sing. He sings the contagious little intro to “Let’s Stay Together,” Al Green’s very first No. 1 hit, and in the next instant everyone is singing too, swaying and clapping and urging the Reverend to join in. These kids were all looking forward to kindergarten when “Let’s Stay Together” was a hit, and there’s no telling how they know it but they all do, every word, every note. The Reverend doesn’t sing at all but simply soaks up the graceful sound of his own song. “I hope the tape’s rollin’,” he says, all smiles.

That very evening the Reverend Green is playing L.A.’s heavenly Wiltern Theater, a green-tiled monument to art deco architecture, a cathedral dedicated to man’s amusement, a glorious ornament. The Reverend James Cleveland, gospel music’s stout patriarch, is in the audience and with him are members of the Hawkins family, Oakland’s famed gospel household. In the audience too is Michael Jackson, surgically masked for secrecy, with the little surgically masked Emmanuel Lewis next to him. Alongside the stars and lesser music business scene-makers are the folks who fill the pews every Sunday, an audience with such very different matters on their minds. The Wiltern is lovely beyond compare, and the sound is marvelously bad, and neither matters a small bit when the Reverend Green walks into the light. Tonight when he reaches his right hand up into the air the Holy Ghost is there, lifts him up, raises him up. lifts him, and will not let him down.

And tonight he brings forth “Let’s Stay Together,” brings it forth in front of just as many church folks as were on hand last night, and he says all those same things he said last night, and tonight there is a glory in it. Yes, and tonight he goes past the glory of his old songs, mighty as they are, and he sings “Amazing Grace.” Just “Amazing Grace,” that simple old song that’s been done all to death and back again. Yes, and he is so filled with the spirit, and so much on fire, and so graceful, so grace-filled. Yes, and this is why people who don’t even faintly believe in Jesus find themselves with tears streaming when they stand back and watch gospel music, find their souls moving in step with their feet, find themselves stirred. Stirred.

And tonight the Reverend Al Green isn’t throwing out any shoes. No, tonight the Reverend is coming forth, is climbing down into the seats, is out among the flock. “It’s alright,” he tells the security ushers, “Ain’t no one gonna hurt me here,” and he laughs as he sings. He’s taken “Amazing Grace” and brought it down so very quiet, so very soft, and brought the audience along to higher ground. Any hand not clapping is raised high in the air, and all over the church — this is church now — the ladies have raised the holy shout, have found the sanctified bounce, have commenced to fall out, shivering, rattling, stiffening. And the Reverend passes through the crowd unmolested, hugging and shaking hands as he sings and delivering the spirit with every sound, every motion, every moment. “Was grace that brought me safe so far,” he sings, and the clapping is so many times louder than the band, “...and grace will lead me on.”

And on the day that follows, on Sunday afternoon, at a time when he would usually be finished with the morning services back home in Memphis and not yet ready to start the early evening Bible study, Reverend Green is quiet in his hotel room, quiet and still. A Bible is at hand and a guitar is in his lap. A little soft pass at the strings, a little soft smile. The sound stays and lingers like the last ripple in a small pond after a rock has skipped the surface and settled to the bottom. It sounds like The Belle Album.

Yes, but nothing else sounds like The Belle Album, not in the ten years since it came out, not ever. You could hear a man’s soul tearing itself in two, then knitting together again, larger and far finer. To make the record, Al Green had to part with his producer, his record company, his audience. He produced the album himself and played guitar, tart and crisp and clean guitar, guitar licks just like the ones he’s messing with this afternoon in his hotel, guitar licks that squeeze time and take you home. ‘Belle was Mary,” he says, watching his fingers where they rest on the strings.

And Mary, Mary Woodson, was a woman who was so very taken with the man Al Green was, she believed she couldn’t live without him. She was already married, although Al has always said that he really never knew it. She proposed marriage to him one night, to the man who sang “Let’s Stay Together,” who sang “Let’s Get Married” and “God Blessed Our Love” and so many songs, and after he turned her down he went and took a bath, She took a pot of boiling water—”lt wasn’t grits like they always say in all the stories, it was water boiling to fix grits”—and she threw it at him, scalded and burned and scarred him with it. Then she took her .38 pistol into the next room and there she died.

The water scarred his back but it may have saved his soul. “Belle,” he sings, “It’s you that I want but Him that I need..." and the guitar is a reflection, the words a calm confession. If the Lord is at the front of his life and at the back too, if Jesus is his All in All, his All and All, if He, if He, He, He . . . And words fail him, and the Spirit moves him, and his voice is triumphant. The storm has stilled, peace reigns. “It was Mary who told me first that I was going to be called,” he says, “that l would have a ministry of my own.” He pauses for a tiny sweet lick on his guitar, sweet and slim and pretty. “I laughed at her. She said I was called and I laughed at her and said ‘Who, me?’ “He laughs again just thinking about it a dozen years later. “She told me.”

In an airplane on the way home to Memphis, the Reverend Green claps his hands at the sight of the California coastline falling away beneath his window, gives the Lord a round of applause for some fine truly wonderful work. Smiling and thoughtful, the Reverend Green is reminded again of The Belle Album, of that same line from that same song, and of how much it meant. “That is the pivotal point right there. ‘It’s you that I want but it’s Him that I need.’ That was a statement that was given because it was given.”

Reverend Green is a man given to mild ways of amusing himself in moments of leisure — holding his red rayon scarf over his face and flicking its tassles across his nose, chewing mints, gum, and peppermint Life Savers, elbow-nudging a fellow passenger when a good conversational point is delivered. He has a tendency to view his own past as someone else’s, to see Al Green as though he were someone removed and remote from himself. “I don’t know why he cut that record,” he will say; “I don’t understand why, as much money as he had, I don’t know why he didn’t go to any studio he wanted. I don’t know what he was doin’, I really don’t understand. I think he did it out of the fact they told him it couldn’t he done, and they told him that if he did do it, they told him the album wasn’t gonna come out in the first place. I think it was a challenge for him more than anything else, and he did it in defiance. I think this is why he did it. I’m not sure. He did a lot of things I’m not sure why he did. I don’t know why. Just brought a 8-track studio down, just rolled it in there on some wheels and plugged it in—I don’t know why he done that. I don’t understand. But it does not go without Mary.”

Picking up an advance cassette of Soul Survivor, his newest album, he turns it over and over, admires the typed titles. “Now, this album relates to vintage Al Green because I don’t hear nothin’ else but Al Green, and him chankin’ on a guitar. If that ain’t Al Green, I don’t want to see it. That’s him for real, without all the make up and the glamour and the beauty. That’s him right there.” He raps on the cassette’s blank cover with his finger. “That is the very Al Green. Without all the cookies and candy. This is the very Al Green, right here in the overalls and bomber jacket, sittin’ here playin’ guitar on the floor.” Asked if he can find any hits inside this cassette, he smiles deeply and points to one and another and another after that. He points to every song but one, and then he includes that one too.

The music that Al Green made in the years before The Belle Album shows no sign of aging, no sign that a time will ever come when it won’t feel perfectly right, It’s pastoral music, always cool and sweet. Al was raised up in the country, on the Arkansas side of the Mississippi, the son of a preacher. There is country in his music, there are Hank Williams and Willie Nelson songs on his old albums, but there isn’t one of his songs, not one of the hits that filled the dance floors through the first half of the ‘70s, that doesn’t somehow suggest just a trace of mud between the toes.

Reverend Green can’t help but laugh and laugh when he considers the wonder of his songwriting. “Cause if you start with ‘Call Me,’ for instance, you start with ‘What a beautiful time we had together.’ He spreads it out flat and simple. “ ‘Now it’s gettin’ late, and we must leave each other. But remember the times we had. And how right I tried to be. It’s all in a day’s work. Call me.’ “ And then he giggles and giggles like a kid caught with his hand in the cookie jar.

By Sunday, the Reverend Green is back in church, back at Full Gospel Tabernacle, just a mile or so down Elvis Presley Boulevard from Graceland. There is nothing monumental or magnificent about Full Gospel, although like everything else in Memphis, it has a portable Rent-a-Sign marquee out front, yellow, with black plastic letters listing the hours of worship services. There is a scroll painted on one of the walls behind the altar that says “Let God Be Magnified.” A painting in back shows lily-pure souls rising to Jesus from out of graveyards, from office buildings, from cars crashed on a freeway and driven into the water, and from a Volkswagen van that has been crushed in a collision with an 18-wheel tractor-trailer rig.

It’s gathering dark outside and windy cold when the six o’clock prayer meeting and Bible study class is close to commencing. The Reverend Green is sitting just off the altar with his guitar player’s Fender in his lap and the amp cranked up, and if this wasn’t Sunday evening in Full Gospel Tabernacle, you’d swear those were blues he was playing. He fingers a few of those mean, mean little obbligatos, those rippling arpeggios, laughs, and goes off to mess with the organ.

When all the ladies are in the pews, there can’t be more than 20 in attendance What is it that would make a man lay down a singing career that showed no sign of stopping, or even slowing down, a man who had thousands of women battling to grab the red roses he threw them from the stage—what would make a man lay it all down to pick up a Bible and preach a Sunday night meeting that is hard-pressed to total two dozen?

The Lord’s Prayer starts the meeting, and a hymn is lifted. Things are settling in—this will be a long night—when one of the ladies asks her pastor if maybe they can sing one more, one she needs to hear. Her mama’s health is failing, she feels like her mama may pass, and she’s worried and troubled in mind.

“Will you lead us?” the Reverend asks her.

The song’s motion is slow and it rolls along deep. She starts it and he joins it and the other ladies are there too, slow and deep. It’s graceful and mighty and the ladies lean on one another’s voices the way tall trees lean in the wind. Two choruses, three choruses, and then the Holy Spirit is joined, the Holy Ghost stirs the hymn, and the song grows too tall to go over, grows too low to get under. It speaks all language and the woman who called for it is sobbing, screaming, praising God, wiping her eyes with a yellow tissue. Another woman stands, so close to falling out, so close, and thanks her Jesus, thanks her Jesus. The Reverend is with them, and in this moment his voice, his wonderful voice, is one of many.

Posted by

Nasrudin

at

3:40 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Al Green, Amazing Grace, Anton Corbijin, Bart Bull, Hank Williams, James Cleveland, Mary Woodson, Michael Jackson, Sam Cooke, Soul Train, the Holy Ghost, the Soul Stirrers, Willie Nelson