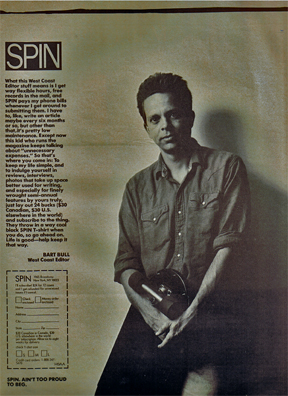

by Bart Bull

(published in SPIN; excerpt from cover story)

It wouldn’t be fair to say that Prince didn’t exist before “I Wanna Be Your Lover,” but it might be right, and it would be true. A song from his second album, “I Wanna Be Your Lover” is a hit on all the black radio stations, and in 1979, that means it’s beneath ignoring. And that wasn’t what Prince had in mind, not at all.

“I Wanna Be Your Lover” is a sketchy, edgy, cocksure set of unrehearsed pickup lines, nervous and confessional, bold and full of brag. He ain’t got no money, he ain’t like those other guys you hang around, and his sound is so stripped and skinnny and spare you can’t help but believe him.

He wants to be your lover. He wants to turn you on, turn you out — a pimp’s phrase — all night long, make you shout, he wants to be the only one who makes you come (just a brief slight pause) running. He wants a lot. Delirious, in love with his own love, he slips it to you that he’s so in love he wants to be your mother and your sister too. He wants all of you.

He sings the song in the simple falsetto of the single-minded, chastely swaying girl groups like the Cookies, the Dixie Cups, the Orlons, and the Chiffons. In a few years, when he’s gathered the momentum of celebrity, Prince’ll spin off pointedly unchaste girl groups, funk bands, solo careers, new wave crossover packages, vanity acts that will splash the charts and succeed with tunes he tosses off in his spare time. But in 1979, the world hardly knows he’s alive and cares even less. This is intolerable. Lacking a girl group, he sings it himself, makes it a Prince record. The first Prince record.

Pitching his voice up high and keeping it there, Prince uses passion’s peak as “Lover”’s bottom line. It’s a hit, but a segregated one, and — the real bottom line — it identifies him in the pop marketplace of 1979 as black. A bad move.

Male or female, that falsetto is indubitably black. The drums are funky, the bass is big, the stuttering guitar swings; ergo (it's 1979), disco. No matter how fine a song it is, no matter how great a record, no matter how it rocks, it’s a tactical error, a strategic mistake. Prince retreats.

It happens that Dirty Mind, the album that follows, is terrific. It happens that it flops. (Prince "The record’s not doing phenomenally well sales-wise, and airplay is pretty minimal . . .”) It also happens that it doesn’t produce anythong like a follow-up R&B chart smash. It almost seems intentional.

“See," says Prince, ”this album, it was all supposed to be demo tapes, that's what they started out to be." Dirty Mind sounds like nothing so much as a one-man Sun Sessions — what could make a rock critic any happier? — with Prince playing Elvis, Sam Phillips, and every other role. It wasn’t like rockabilly except in spirit; it was a new thing, a hybrid, a deliberate act of miscegenation — musical race-mixing at a time when anything that resembled a contemporary black influence was being quietly escorted out of “rock,” when a white disc jockey inspired a riot of support by burning “disco” records on a major league baseball field.

Dirty Mind wasn’t so much funk as it was funkish; funk was fitted in and around the springy stiff rhythms of the newly-minted new wave. “So they were demos,” Prince said, “and I brought them out to the coast and played them for the management and the record company. They said, ‘The sound of it is fine. The songs we ain’t so sure about. We can’t get this on the radio. It’s not like your last album at all.’ And I’m going, “But it’s like me.”

The me that Dirty Mind is like is a typically oversexed teenager (though he’s 21 now), a true romantic, an uncontainable talent, a guitar hero, a studio whiz, a guy who believes the letters section of Penthouse with all his heart and soul, a very singular case, an exception. And he’s a mulatto, born and bred in Minneapolis, the northern-most cosmopolitan center of the Mississippi river, a place that manages to be a river city and a prairie junction simultaneously. Light enough to pass for white but not quite. Black enough to be completely ignored.

The black and white cover of Dirty Mind shows him stripped down to a bikini and a bandanna, his back against a bedspring. The making of the album had been an exclusive affair, a party in the privacy of his own imagination. It revealed that Prince considered himself a rebel, a sexual politician, a utopian visionary, a pundit. but there was also a photo of a band that made it clear that Prince had every intention of extending his fantasies into the real world. Like the record, his band was black and white, male and female, and they were pushing the new wavey two-tone motif of the checkerboard to its most obvious, most dangerous conclusion. The Minneapolis of Prince’s mind had one small section, “Uptown,” where somone — maybe anyone — could live in simple defiance of society’s expectations. Uptown was the kind of place where Prince would not only fit but be the center of attention. Uptown was dancing, music, romance, and all that came after.

“Soon as we got there,” he sang, “good times was rollin’/ White, black, Puerto Rican, everybody just a-freakin’ . . . ” And freakin’ was, of course, street slang for sex. Like more men than would ever acknowledge it, admit it, or even just get it, Prince has an abiding faith in his dick as divinely inspired dousing rod.

It points him past pleasure toward passion and past passion toward epiphany. And after epiphany comes an instant of relaxation, a brief moment for reality to resume, and for his revulsion to set in. Beyond all else in Prince’s work can be seen a strategy that he creates to control and contain, a defensiveness. His band and the bands that come under his rule dress just the way he wishes them to, sluttish Barbies and Kens, strutting through the purple satin fantasies of a single very inventive adolescent. His own adolescence was likely a lonely one and the first Uptown he ever encountered was the one in his dreams, peopled by porn photos popped to life, and set in the milky mist of fantasy. With a boyhood spent behind closed doors, practicing and preening, playing a guitar and jerking off are exactly the same gesture to him.

Tuesday, April 21, 2015

Prince: The First Prince Record

[Part One];

Posted by

Nasrudin

at

12:00 PM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Bart Bull. SPIN, disco, Prince

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)